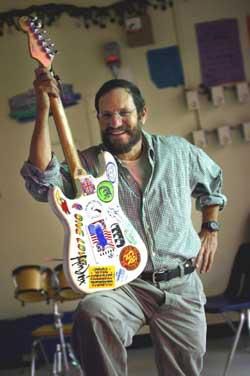

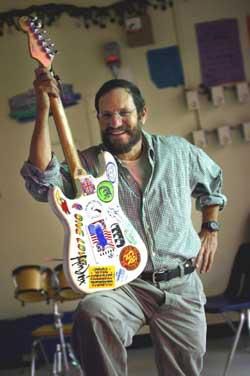

MARSHA HALPER/HERALD STAFF

MUSIC MAN: Dr. David Lazerson, now teaching in Broward County, had a role in ending '91 racial strife in Crown Heights.

MOVIE TELLS HOW PEACE EMERGED FROM

RIOTS

FRED TASKER, ftasker@herald.com

MARSHA HALPER/HERALD STAFF

MUSIC MAN: Dr. David Lazerson, now

teaching in Broward County, had a role in ending '91 racial strife in Crown

Heights.

It could have been West

Side Story: Jets and Sharks meeting tensely on neutral ground in confrontation

over the dangerous dalliance of Tony and Maria.

But this was real: Young Hasidic Jews with beards

and black fedoras, Caribbean blacks in dreadlocks, called together at P.S. 167,

a middle school in Brooklyn's Crown Heights neighborhood, in 1991 after three

days of riots that began when a Jewish driver ran over and killed a 7-year-old

black youth.

``You could cut the air with a knife,'' says

Dr. David Lazerson, a rabbi who was a key leader in the dramatic aftermath and

who has since moved to North Miami Beach and now teaches in the Broward County

schools. ``Both sides looked very ethnic. We realized that, even though we had

lived together for 20 years, we knew almost nothing about each other.''

The dramatic turning point that took place that

night will be portrayed in a TV movie, Crown Heights, starring Howie Mandel

as Lazerson and Mario Van Peebles as the Rev. Paul Chandler, a black Brooklyn

youth leader, at 9 p.m. Monday on Showtime. (Van Peebles' character in the movie,

``Paul Johnson,'' is a composite of Chandler and Richard Green, another youth

leader involved.) The film grew out of Lazerson's memoir, Sharing Turf.

The Crown Heights the two men remember was a

tinderbox: Built around 1900 with palatial homes and apartments, later going

lower-middle-class, with Caribbean blacks moving in to escape the turmoil of

the islands' fight for independence and Eastern European Jews fleeing the Holocaust.

``They competed for jobs, housing, public assistance,''

says Lazerson.

That hot, sticky night in August 1991, a Jewish

driver escorting the car carrying the Hasidic community's leader, Rebbe Menachem

Schneerson, accidentally ran over 7-year-old Gavin Cato, killing him. It happened

just as a reggae concert was ending, spilling hundreds of black youths onto

surrounding streets.

Charges flew over whether a volunteer Jewish

ambulance aided the Jewish driver, leaving the black youth to an arriving public

ambulance. Groups of youths clashed on the streets.

``All hell broke loose,'' Lazerson remembers. ``People were throwing bottles,

turning over cars.''

In the chaos, a young Hasidic man, Yankel Rosenbaum,

visiting from Australia to study the Holocaust, that night going to get a haircut,

was stabbed to death by a black youth. In three days of disturbances, 183 were

injured.

The middle school meeting was called by Lazerson,

a teacher who was drafted by community leaders because he had written a book,

Skullcaps and Switchblades, about inner-city schools in Buffalo; and Chandler,

a self-described former revolutionary whose student protests at the University

of Massachusetts at Amherst against South Africa's apartheid policy in the 1970s

had ended with students closing down the campus.

With violence still threatening outside, the 50 youths in that meeting were

in for a surprise:

``Dr. Laz,'' as Lazerson calls himself, strode

to the front and launched into his very personal rap:

I know it's been said about a million times before,

But change don't come easy, so you got to know the score.

Looking for a friend, a lifelong brother?

You can't judge a book by looking at the cover.

The first reaction was silence. Then a surprise

from the crowd: Tentatively, then urgently, the two sides began peppering each

other with questions:

``What's with the dreadlocks?''

``What's with the hats?''

``How come you Jews are always in such a rush

on the street?''

``How come you blacks are always loitering?''

``All the stereotypes came out,'' Lazerson says.

But the fact they asked questions instead of

spewing hatred gave the two leaders hope.

``We were able to plant some seeds,'' Chandler

says.

From that night grew Project CURE (communication,

understanding, respect and education) as the leaders scrabbled for activities

to bring the two sides together.

``We held joint Hanukkah/Kwanzaa celebrations,'' Lazerson says. ``We started

a black/Jewish basketball team.''

A year later the New York Knicks, holding a ``Racial

Harmony Night,'' let Project CURE's blended team take the floor for a scrimmage

at halftime. ESPN covered it; invitations followed from Montel Williams and

Phil Donahue.

``It expanded way beyond Brooklyn,'' Lazerson

says. ``We had German skinheads coming to us for advice.''

They put together a band: ``Dr. Laz and The Cure,''

made up of Lazerson, a guitar, harmonica and banjo player; Chandler, a veteran

singer and songwriter from his protest days; and youths from Crown Heights.

Today the band tours campuses: Skidmore, King's

College and others. It amuses Lazerson that schools tend to book Dr. Laz shortly

after appearances by divisive racial groups; he thinks it's to get them out

of hot water with nervous donors.

The band disarms college students with a blend

of humor and pro-peace passion. The two men stride on stage in black fedoras,

looking like the Blues Brothers. Chandler surprises the audience by launching

into a song in Hebrew; Lazerson does his rap.

At song's end, Lazerson hollers: ``Yo.''

Chandler protests: ``You don't say `yo.' You

say `oy.' ''

``Same thing, only backward,'' Lazerson answers.

In the late 1990s Lazerson moved to North Miami

Beach. He teaches music in special education classes in Broward County and leads

psychology classes at Florida International University.

IN THE FILM: Mario Van Peebles, left, and Howie Mandel star in the TV movie

Crown Heights. Peebles' character in the movie, ``Paul Johnson,'' is a composite.

Mandel plays Dr. David Lazerson.

In Crown Heights today there is peace if not

perfection.

``It's a lot better than it was,'' Chandler says,

``although I don't think we have the model community I'd like to see.''

If nothing else, the two have validated their

``Increase the Peace'' slogan, the diversity approach they coined on the spot

in that middle-school classroom in 1991. As that meeting ended, Chandler took

a big chance.

``C'mon, let's circle up,'' he called out. Turning

to the gesture he used to end meetings in the other youth groups he served,

Chandler asked the black and Jewish youths to join hands in prayer.

To his joy, they did. As he was about to begin,

he remembers somebody muttering, ``Better keep it nondenominational.''

They found common ground in the Old Testament: Chandler recited the 23rd Psalm in English, Lazerson in Hebrew.